|

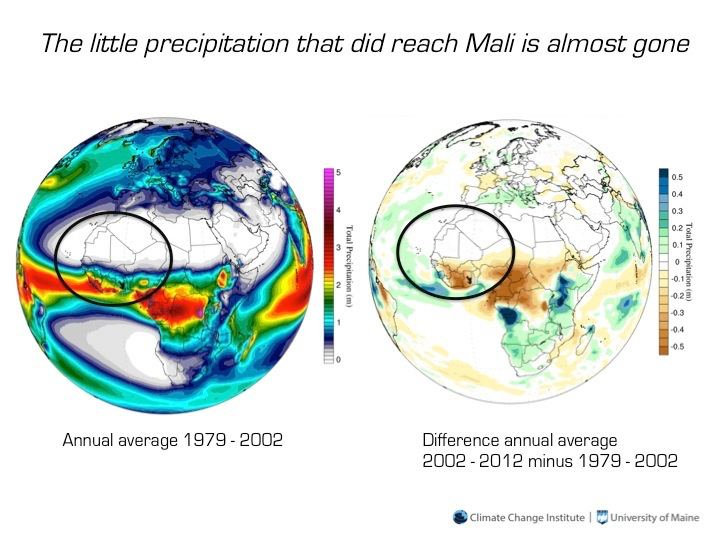

by Paul Mayewski I recently had the pleasure of appearing in the last episode of the award-winning Years of Living Dangerously series produced by James Cameron, Arnold Schwarzenegger, David Gelber, and others. The host for our section, M. Sanjayan, and a film crew joined our expedition to Tupungatito in the central Andes where we recovered an ice core from close to 20,000 feet. You can see his write up of his experience with us here. We now know that a major result of greenhouse gas warming is changes in large and small scale wind patterns around the globe. The details of exactly when, where, and how much rain falls can have significant implications: Tom Friedman made the case that drought in Syria and surrounding regions played a significant role in the emergence of unrest that led to the Arab Spring. For many farmers around the world, even a small shift that takes rain away from their fields can mean the difference between a good life and becoming a refugee. The purpose of many of our expeditions, including this one, is to discover how increasing greenhouse gases and high-altitude ozone depletion are changing wind and precipitation patterns, allowing better predictions of how water, heat, and pollution are moved around the planet. Our Tupungatito study site, located at the northern edge of the Antarctic Westerlies, provides unique insights into these changes. Shifts in moisture bearing winds are not only leading to drought in the Middle East but also in Africa, Australia, and the western US. The politically unsettled west African country of Mali, home of 14 million people, has experienced significant drought in recent years. The northern two thirds of the country has seen severe drought for decades, while the lower third received enough to grow crops. But, in the last few years, this “wetter” lower third has lost more than half of its usual rainfall, leaving this landlocked country in a critical state. Understanding where, how deep, and how long drought will occur is essential to geopolitical, economic and most importantly humanitarian efforts.  The little precipitation that did reach Mali is almost gone. The map on the left shows average annual precipitation. Mali, circled, receives almost no water in the north and much more in the south. The right map shows the change in precipitation as the 2002 to 2012 average minus the 1979 to 2002 average. The amount of rain now reaching southern Mali is greatly reduced. Plotted using Climate Change Institute Climate Reanalyzer™ software. Comments are closed.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed